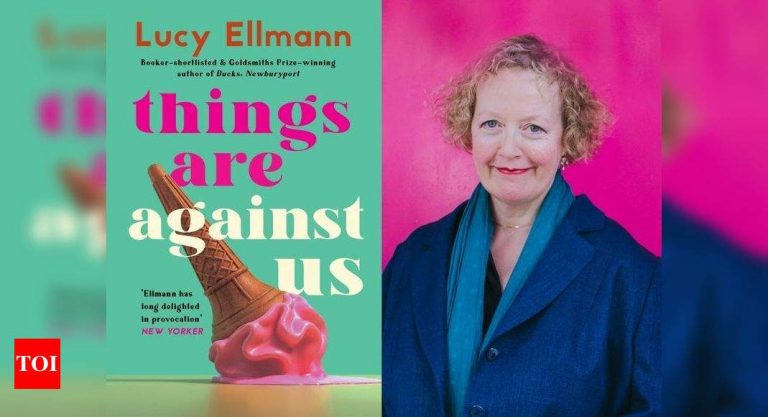

British-American author Lucy Ellmann was nominated for the prestigious Booker Prize 2019 for her book Ducks, Newburyport. And now, the author has penned Things Are Against Us, a collection of angry yet funny essays. Things Are Against Us is Ellmann’s ninth book, wherein she shares her no holds barred opinions on various topics like patriarchy, the environmental crisis, and Donald Trump’s chaotic presidency in the United States among others.

In an exclusive interview with TOI Books, Booker 2019-nominee Lucy Ellmann tells us about her new book, why her writings reflect anger and despair, her thoughts on crime fiction writing, her all-time favourite books, writing tips and more.

1. The narrator in Ducks, Newburyport is a mother of four who is dissatisfied with the state of the wider world. In your new book Things Are Against Us you share your opinions on things going wrong in our world… Are the two writings interconnected in a way – did one book lead to the other? How was working on the essays different from your other books?

My take on the world is that humanity sucks and we have ruined the earth. All my books reflect this cheery view. In the essays, though, I deal with a small slice of something that bugs me, not the whole shebang, and employ hyperbole, fury, caprice, grumbling, exaggeration, and wild guesses, all in aid of a good cause: defiance.

Because it’s time to get angry. The entire world’s in a tailspin and we need to get a grip. Let’s save the birds, bugs, animals, and plants, Bach, Titian, and Shakespeare, quilts, Satyajit Ray movies, Burkino-Faso printed fabrics, and regional cuisines, but dump computers, space missions, nuclear power, Twitter, Fox News, despots, gangsters, armies, capitalism, and corporations.

With essays, you don’t need plot and characters, you can let it rip. I think fiction provides the deeper truths, but nonfiction can be exhilaratingly direct. These essays were surprisingly fun to write. I just hope people still get satire.

The ‘I’ in my nonfiction is ME, more or less, which is a lot more straightforward than the way you build a first-person character in fiction. The narrator of Ducks, for instance, is not much like me except that our minds work along similar lines, and we’re both bombarded by the news, family matters, social dilemmas, and small painful objects underfoot. My Ohio narrator is intentionally a lot more patient and conciliatory than I am, and apolitical almost to the point of apoplexy. I had higher hopes of her daughter being stroppy enough to get something done about the Republicans and climate change and mass shootings and white supremacy. A tall order, I know, for one confused and isolated youngster.

2. What was the inspiration behind your new essay collection?

A mixture of things. The title essay, “Things Are Against Us”, is a goofy foray into paranoid nonsense built on the suspicion that inanimate objects are out to get us. “Sing the Unelectric” and “The Lost Art of Staying Put” touch on climate change, and the ridiculous ways in which people are using up the last of the world’s resources on fake pleasure-seeking, which is really just a clandestine form of boasting.

Most of the essays, in one way or another, make the case for matriarchy. And why not? Women couldn’t do a worse job of running things than men have. We have form too: it seems clear that human society was largely matriarchal for a good two hundred thousand years or more. This produced peaceful, artistic, agrarian cultures that honoured women as crucial figures in society. They were not just there to wear the high heels and fry the chicken.

Matriarchy is a subject I’ve alluded to in many of my novels too – particularly in Mimi, the tale of a rich New York plastic surgeon who falls in love with a rebel and succumbs to feminism. So it seemed high time I looked at the matter objectively, in the form of some crazed nonfiction.

3. Your writings in both the books reflect anger and despair. Why so?

It’s healthy, I feel, to nurture a high level of scepticism and self-contempt. Humans need this in order to develop the humility to quit being a menace to the natural world. And I need anger and despair in order to write. (Also, a little wonderment.) I tend to explore my resentments until they start to amuse me.

4. What is your one piece of advice that you would like to share with aspiring writers?

Resist the present tense. It is SO BORING. It’s brittle, flat, and inflexible. It has a deadening effect on anything you write. People use it almost uniformly these days, presumably in the belief that it will make their work more immediate or down-to-earth. It won’t. Why cripple yourself this way? The past tense has twenty times more beauty and nuance. Sure, use the present when you really need it, but don’t treat it as the answer to every writing dilemma.

And don’t screw around with chronology unless you absolutely must. This is another new fad. Everybody’s doing it. News alert: jumps in time are not artistically adventurous, they’re distancing. You are giving yourself, and the reader, more work to do.

5. In an earlier interview, you shared that you don’t tend to read contemporary fiction. So which are your all-time favourite books and authors?

I like funny writers. The fiery and sincere too, as in Hardy’s work, or Brontë’s Jane Eyre, and the irrepressible Walt Whitman. But life would be poor, nasty, and brutish without the jokes of Rabelais, Chaucer, Sterne, Austen, Dickens, Joyce, Beckett, Narayan, Nabokov, Salinger, Molly Keane, Thomas Bernhard, Elfriede Jelinek… The Fan Man, by William Kotzwinkle, is another favourite. Flaubert’s nicely ironic, and Tolstoy too can be inadvertently sardonic. The Kreutzer Sonata’s quite comical at times about the battle between the sexes. The homicidal husband claims that, since the mercantile realm (shopping) is largely aimed at them, women must have all the power. Like most murderers, he’s got everything backwards.

6. Have you recently read any works by debut authors? Would you like to recommend any of their works to our readers?

Two aquatic titles for you, though neither of these books is really all that watery. Pond, by Claire-Louise Bennett (Fitzcarraldo, 2019), a collection of seemingly autobiographical stories, is witty, nutty, endearing, and unexpectedly substantial. One story concerns the wonky knobs on a tiny cooker, another deals with bananas. And she is often poetic: ‘I would listen to a small beetle skirting the hairline across my forehead. I would listen to a spider coming through the grass towards the blanket.’ Somehow, Bennett manages to be cunningly profound yet lithesome about the stolid facts of existence.

Wave, by Sonali Deraniyagala (Virago, 2013), is a fearless, honest and probing account of acute grief, written by a Sri Lankan economist who lost many members of her family in the 2004 tsunami. She refuses to shrink from the complexities and perversities of her own mourning: the fury, the drinking, the guilt, shame, madness, and alienation. Nothing means much to her for a very long time. But gradually Deraniyagala, a born writer, regains her family in a way, by recreating them on the page through memory. I dare you not to cry.

7. In one of the pieces in the book, you say that fiction, especially crime fiction, glorifies violence against women. Why so? Please elaborate…

Isn’t it enough that men really do rape and kill women, without having to read fictionalised accounts of these atrocities as well? I think such tales are used to scold and alarm women and keep us in our place. Some crime novels and movies may also offer a few pointers on self-defence, but the main purpose of these fables is not only to prolong the oppression of women but to exult in it. I’d rather exult in hoola-hooping than in horror, gore, and autopsies.

Aren’t human beings morally degraded enough already? Do we really need to concern ourselves nightly with severed limbs? Crime is not the only kind of transgression available to us, after all. How about guerrilla knitting or over-eating, or dancing naked for the moon? Let’s get creative around here.

8. You write, “Everything women do is taboo. Anything men can do, women can do better – but somehow, everything women do, men say stinks.” And it’s true even in India – be it in the house or in a corporate setting. How can women deal with this casual sexism, according to you?

Sexism’s never ‘casual’ – it’s all part of a sinister experiment in mass hypnosis. Like racism, sexism doesn’t make any logical sense: there is no way that one could truly believe that women are inferior to men, or less deserving of admiration. But human beings have been pretending just this for five thousand years! What goofballs we are.

My solution is peaceful revolution, starting with globally organised women’s strikes: a housework strike, a labour strike, and a sex strike. If these deprivations don’t drive men crazy, nothing will! No cooking, no cleaning, no mopping of the manly brow. No kissing, no cavorting. A few weeks of this and we’ll have men lambasting themselves all over the world and begging for forgiveness. Out of pure self-interest, they will race to make amends.

But I’m also tired of women having to repair men’s mischief. Why can’t men revise their idiotic attitudes by themselves? Men should sort this out, because women are exhausted. Men must voluntarily renounce all the tricks they’ve played on us and admit their own complicity. Men who go along with discrimination against women, men who put up with porn and prostitution and other men’s misogyny, men who claim to need man caves in which to chill out and drink beer while starving women queue for bread, men who jabber when they should be listening to what women have to say – such men are all servants of patriarchy, the grand conspiracy erected to deprive women of rights, self-esteem, hope and justice. Cynics may feel injustice is not that big a deal, but cynics have lost the plot. Without justice, all we have is barbarity.

We must never let them off the hook. Never stop criticising their appalling decisions, their distracting antics, their belligerence, arrogance, indifference, and insouciance. Their eternal attempts to deprive women of life, liberty, and happiness. We must never shut up about it, never let it rest. And for godsake, could we just stop trying to please the silly fellows all our born days? It’s MEN who should be pleasing US.

(DISCLAIMER: Views expressed above are the author’s own.)

.