In the first week of April, Manoj Tomar, 40, a daily wage earner from JP Nagar in Old Bhopal, got a cough and fever that wouldn’t go away. A breathless Tomar, suspecting he had Covid, looked for a testing centre but there was none nearby. On April 7, he went to a local quack, a “jhola chhaap” doctor. A rapid antigen test detected the Covid virus in his body, but Manoj could not find a bed at any of the government hospitals. Later that evening, he died. A week later, his brother Jitendra, 38, also developed symptoms but was able to get himself admitted at the Government Hamidia Hospital, where he too tested positive for Covid. Later, he also died. While the family got a death certificate from the hospital stating that Jitendra had died of Covid, they had no such luck with Manoj.

The story of the two brothers from Bhopal illustrates the irony in India’s management of Covid dead statistics. The importance of an accurate death count came into focus again following a recent Supreme Court order asking the Centre to pay ex gratia compensation to the families of those who had died of Covid (see box below Will the Covid deaths imbroglio impact compensation?). A PIL in the top court has also pointed out that the non-reporting of Covid as the cause of death could deny government compensation to many affected families. But now a bigger challenge arises for the system—creating an accurate, comprehensive list of eligible claimants. With compensation being made mandatory, many, like Manoj’s family, will now be scrambling to get that elusive death certificate that puts down Covid as the cause of death.

The official death toll in India, the second most populous country in the world, has certainly not reflected those horrific images that played out on national television, particularly during the second wave—people gasping for oxygen, long queues in hospitals and crematoriums, the incessant sirens of vans carrying bodies, and then the bodies floating in the Ganga in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. It was evident that India was no exception to the rule—the World Health Organization estimates that the deaths globally could be 2-3 times the officially reported numbers. The Economist, using a mathematical model, had estimated around one million Covid-19 deaths in India as on May 15, as against the official tally of 270,319. Another article in The New York Times claimed that up to 5-7 times more people may have died above and beyond the official count.

The Union government dismissed these studies as “unsound analysis” and extrapolation of data “without any epidemiological evidence”, but the subsequent reconciliation of death numbers by various states indicated there were huge gaps between the official Covid-induced death count and actual numbers of the deceased on the ground. In June, at least six states—Maharashtra, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Goa, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab—revised their death count, resulting in a sudden spike in official records. And the numbers are growing with every revision. India isn’t the only country to see such a reconciliation. Even in the US, states such as Indiana, Oklahoma and Maryland have noted backlogged deaths.

The recount in the states was triggered by several factors, including the announcement of compensation for Covid victims, court directives and media reports exposing the undercounting. The announcement of compensation by several states naturally led to an uproar as many families were likely to be denied it as the deaths were not recorded as Covid-induced. In Bihar, for instance, the government was forced to do a 20-day exercise to audit Covid deaths after the Patna High Court red-flagged discrepancies in figures cited by different agencies in one district. The court was hearing a PIL on reports about corpses floating in the Ganga. In Maharashtra, the recount began following newspaper reports on unreported Covid deaths.

What is the real Covid toll?

However, even the latest disclosures may still not provide the true picture. The all-cause mortality numbers from India’s Civil Registration System (CRS) of various states show a massive jump in excess deaths, hinting that the extra mortality may have been due to the pandemic. Excess deaths are typically defined as the difference between the observed numbers of deaths in a specific time period in a year and the number of deaths in the same time period in another year. In national capital New Delhi, the comparison of CRS data shows that April 2021 had 242 per cent more deaths than April 2020.

Down south, the Tamil Nadu government’s CRS revealed that over 142,000 more people have died between January 1 and June 25 this year, as compared to the same period in 2019, a non-Covid year. Of these excess deaths, only 19,929 were recorded as Covid deaths, as per the official health bulletin. More importantly, the bulk of the excess mortality in Tamil Nadu happened between April and June when the second wave was at its menacing peak.

In the same period, the CRS data for Madhya Pradesh revealed 42 times excess deaths; they were 34 times more in Andhra Pradesh and five times more in Karnataka. The four states—Tamil Nadu, MP, AP and Karnataka—are home to 21 per cent of India’s population. Together, they have shown half a million excess deaths in the first five months of 2021, but they report only 46,000 Covid deaths. In the Telangana capital Hyderabad, in the first five months of 2021, excess deaths were 8.2 times the official Covid toll for the entire state.

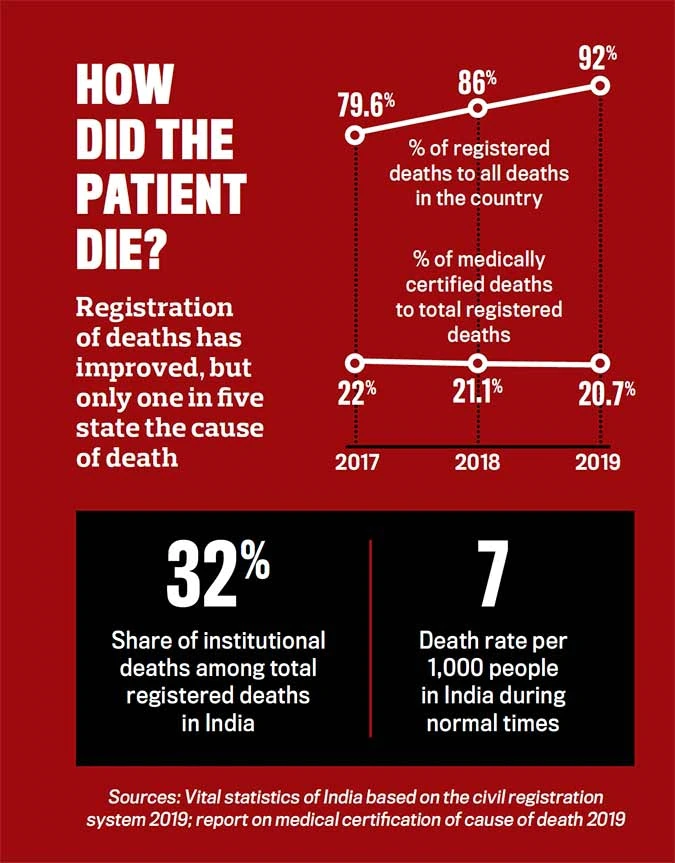

Several experts, however, caution against “inferring too much” from the CRS data. One reason behind the hike in excess deaths is the continuous improvement in the death registration process in India, resulting in better data management. Data recently released by the Census department of India shows that 92 per cent deaths were registered in 2019, up from 66 per cent in 2011. This also marked the ninth consecutive year in which death registration rates showed an increase.

Besides, the pandemic indirectly killed many people who were not infected but had other serious ailments. As medical infrastructure got overburdened with Covid management, many of these patients could not access critical care, and some succumbed. “The CRS data could be a good indicator for understanding the devastation caused by the virus but let’s not forget that a large number of non-Covid deaths also happened this year. Lack of beds in hospitals as well as the restrictions on movement due to lockdowns led to many deaths as treatment could not be given in time,” says K. Sujatha Rao, a former Union health secretary.

The missing cause of death

Despite the national improvement, India’s performance has been abysmal in terms of attributing cause while registering a death. The scheme of Medical Certification of Cause of Death (MCCD) under the Registration of Births and Deaths (RBD) Act, 1969, makes it mandatory to provide cause of death for registration. Yet, as the annual MCCD report for 2019 shows, only 20.7 per cent—or one in five—registered deaths in India mentioned cause. It is less than one in 40 in Bihar, about one in 30 in Jharkhand and one in 25 in Uttar Pradesh. Even in states like Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, which boast 100 per cent registration of deaths, only 11-12 per cent are medically certified with a cause of death. What’s even more worrying is that the share of medically certified deaths across the country has seen a dip over the years—from 22 per cent in 2017 to 21.1 per cent in 2018.

Even in cases where the cause of death is recorded, norms are not followed most of the time. The form used for death certification is based on WHO guidelines, which stipulate that the immediate cause and all underlying causes must be identified and certified by a doctor. In 2016, when a special team commissioned by the Registrar General of India (RGI) to assess the status of civil registration visited Bihar and Assam, it found that in almost every form certifying death, the doctor stated that the person had died of ‘cardio-respiratory failure’. ‘This did not explain anything. There is no other way that death comes, except through failure of the heart and breathing,’ wrote former IAS officer Gopalan Balagopal, who led the team.

So it’s not surprising that, in a pandemic year, despite the sudden spike in the number of deaths, the majority of cases have been registered without a cause of death (particularly when it happened outside hospitals/ medical facilities). The provision for MCCD was extended to all medical facilities in 2012, but this has not had much effect on the ground. In India, only 32 per cent of the total registered deaths are institutional deaths. “The deaths which happen in hospitals are always certified for the cause. However, the quality of the death certification and the description of underlying causes are usually non-standardised. The WHO norms are hardly followed. Deaths that happen outside hospitals, such as at home, are merely registered and medical certification of causes is usually not done,” says Dr Chandrakant Lahariya, an epidemiologist and public health and policy expert.

What has also added to the non-reporting of many Covid deaths is the insistence that only those who tested positive could be considered as such. According to ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research) guidelines, even suspected cases (which have not been confirmed through testing) should be reported as Covid deaths. But many states did not record deaths as due to Covid in the absence of positive test results.

On October 9, 2020, the Union ministry of health and family affairs issued a letter to all states and Union territories (UTs), saying that all deaths with a diagnosis of Covid, irrespective of comorbidities, must be classified as due to Covid-19. The Centre declared that anybody who failed to register Covid deaths—even the certifying doctor—would suffer penal consequences under Section 188 of the Indian Penal Code. Experts, however, say waving the stick is not the answer, strict adherence to a more specific and a standard way of classification is. But that’s often not the case. For instance, many uncertain deaths are certified as ‘infection’.

Even in a state like Kerala, which has better health indicators and awareness than most, there are debates over the under-reporting of the death toll. In July last year, Dr Arun N.M., who practises general medicine in Palakkad district, was the first medical professional to challenge the official Covid death data. “I had doubts as the state government dashboard on Covid changed its style of reporting the deaths. Later, I learnt at least six deaths in my area were not recorded,” Dr Arun told INDIA TODAY.

In the first wave, the non-reporting of Covid deaths was more in rural areas, where there was a dearth of testing facilities. The stigma associated with Covid deaths also forced many, particularly in the villages, not to report such deaths which occurred at home. Experts say that at an existing death rate of seven per 1,000 people, an average village of 1,000 people should report around one death every two months. But most Indian villages have experienced deaths at a far higher rate in the two months of the second Covid-19 wave. According to Dr Manas Gumta, general secretary of the Association of Health Service Doctors in West Bengal, under-reporting is happening because around 70 per cent of people living in rural areas prefer to visit quacks to avoid testing and getting quarantined. “The actual number of deaths is definitely at least three times higher. There are many, many places in Bengal without any organised crematoriums or burial grounds and panchayats issue death certificates without attributing the cause of death,” says Dr Gumta.

During the second wave, as the number of infections grew alarmingly, there was massive pressure on hospitals and testing facilities even in urban areas. A large number of people died without getting access to testing or medical facilities. In many instances, patients died even before test results came in. Many of them did not make it to the officially reported list of Covid deaths. There were also political reasons for keeping the numbers low. “Some states wanted to show they were managing the pandemic better. So, the Covid deaths were not attributed to the virus,” says Rao.

Why is the death count important?

The experts say this gap in attributing the exact cause of death may hugely handicap India’s fight against Covid. The cause of death is extremely important in assessing the effectiveness of public health programmes. They help in determining priorities of health and medical research programmes and provide feedback for future health policy, planning and implementation. “Understanding the causes of death is essential for health sector planning and optimal allocation of health resources. In the absence of robust data on the causes of death, governments are forced to rely on estimates,” says Lahariya.

While several states have now begun revising the Covid death count, there is a need for a systemic overhaul. One immediate corrective step should be a ‘verbal autopsy’ of the dead, especially in rural areas where there is no doctor to identify causes of death. Cause of death is ascertained here on the basis of information provided by non-medical people such as family, relatives and neighbours of the deceased. The RGI introduced the Physician Coded Verbal Autonomy (PCVA) to estimate disease burden as part of the Sample Registration System (SRS) in 2003.

A verbal autopsy can fill a critical gap in measuring Covid mortality outside of healthcare settings and in rural areas. Jharkhand was the first state to conduct verbal autopsies during the pandemic. The state did a door-to-door count in April and May 2021, and added nearly 25,500 more Covid-19 deaths—43 per cent more than the reported data. Jharkhand’s example has proved that the verbal autopsy route is quite doable. The state surveyed 66 per cent of its population with the help of the existing workforce in just 10 days.

Both the Centre and other state governments must emulate such practices. At the same time, a national initiative must begin to ensure mandatory and accurate certification of the cause of death through stricter enforcement and higher awareness.

Will the Covid deaths imbroglio impact compensation?

With state borders closed, many people were unable to take the ashes of the dead for immersion. At Delhi’s Lodhi Road crematorium, the urns pile up, May 9; Photo by Chandradeep Kumar

A PIL filed in the Supreme Court claims that the non-reporting of Covid as a cause of death will deny state compensation to the families of genuine Covid victims. The petition pointed out that many such deaths were shown as due to heart or lung failure and demanded that the immediate kin of every Covid victim be compensated with Rs 4 lakh as provisioned under the Disaster Management Act (DMA), 2005, for a notified disaster.

On March 14 last year, the Centre notified the Covid-19 pandemic as a national disaster. But in response to the PIL, the government submitted an affidavit ruling out ex-gratia compensation while pleading that its finances were under severe strain.

The top court, however, rejected these arguments and, on June 30, directed the Centre to frame within six weeks uniform guidelines on ex gratia payments to the affected families. It also noted that the Prime Minister-headed National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) “failed to perform its statutory duty” by not envisaging a compensation scheme.

Meanwhile, some states announced ex gratia payment on their own for Covid deaths. The Delhi government announced Rs 5 lakh to the kin of those who died due to shortage of oxygen but only Rs 50,000 for other Covid deaths. Bihar announced Rs 4 lakh as ex gratia compensation, MP and Karnataka Rs 1 lakh. But in Karnataka, only BPL families are eligible. Former Union health secretary K. Sujatha Rao sounds a word of caution: “Compensation is needed, especially when children have been orphaned. But it should be announced only after we have robust data on death. Or it could lead to massive forgery.”

|

How deaths are registered in India

India’s Registration of Births and Deaths Act, 1969, mandates compulsory recording of births, deaths and stillbirths, including the medical certification of cause of death (MCCD). It is mandatory to register the death before applying for a death certificate. The death must be registered within 21 days of its occurrence with the concerned local authorities. The certificate is then issued after proper verification. Apart from other documents proving identity and address, the application must be submitted with a medical certificate of the cause of death. In most occurrences of death, particularly at home and under natural circumstances, this medical certificate is neither sought nor attached. The Civil Registration System (CRS), managed by the Registrar General of India (RGI), is the repository of all the records pertaining to birth and death for all states and UTs. The vital statistics data generated through CRS is quite useful for medical research and policy making in terms of healthcare and infrastructure.

|

—with Jeemon Jacob and Romita Datta

.