P .V. Sindhu had just won her second Olympic medal and the few of us from India who were in the stands at the Musashino Forest Sport Plaza were understandably ecstatic. After all, Olympic medals are still hard to come by for India, and Sindhu is the happy exception who lived up to her billing, with back to back medals on the world’s biggest sporting stage.

Sindhu knew I’d press her for an exclusive interview, and was happy to comply. But these were exceptional circumstances, and the Covid-safety norms at the Tokyo Games were understandably stringent. Neither of us knew, though, at the time how difficult it would be to pull off what is now, between us, a routine post-match/ event ‘exclusive’. As soon as she emerged from the mandatory post-match dope test, the organisers made for Sindhu, to shepherd her to the safety of the athletes’ room. Stepping out for the interview would be a breach of government-mandated protocol, and the warning was stern: “You can’t return to the athletes’ village if you go with him!”

By this time, the television newsroom back home was in a state of panic, dreading that the much-anticipated interview would not materialise. After much persuasion, Sindhu was allowed to do a print interview (no cameras, please!), in the press conference room, with an official on watch to ensure we kept the mandated safe distance of six feet between us. There had to be another way.

Sindhu left for the Games village and I got on the media bus for my hotel—but only to get off midway once she messaged. We eventually recorded the interview at 3 in the morning, on a Zoom call, in some nondescript place en route! What she told me was worth the struggle: “There was a lot of pressure and I knew people back home were expecting everything. I kept that emotion aside when I played and gave my best. It’s not easy. It’s a lot of hard work. Now I’m super happy.”

Tokyo 2020/21 has been by far the most difficult Olympic Games to cover. But the insistence on these sometimes-painful protocols is also the reason why the Games organisers managed to pull it off. Despite all the doomsday predictions, Covid cases among key participants—officials, athletes, contracted staff and media—never exceeded the 0.02 per cent mark, and the Games, by and large, went off well.

The same cannot be said of the underwhelming Indian campaign, the odd highs notwithstanding. There were some breakthrough performances, but the hope of a double-digit medal haul, which appeared realistic when we left India, remained a hope for later. The shooting team had their second consecutive barren Games; the archers belied their promise; boxers like Vikas Krishan and Amit Panghal failed to live up to the hype; and some like Chirag Shetty and Satwiksairaj Rankireddy in badminton were unlucky to not make it to the quarter-finals even after winning two of their matches.

But even in the midst of these disappointments and a persistent medal drought, there were uplifting stories of gutsy effort. Nobody would have given the women’s hockey team a chance against three-time Olympic champions Australia. Yet Rani Rampal, who took to hockey to ensure she was able to build a pucca house and eat two full meals a day, inspired her girls to do a Chak De! India. An unfancied team defied all odds against the best in women’s hockey, writing an inspiring renaissance tale even though they lost in the semis. The scenes at the Oi hockey stadium, the girls crying for joy and Hindi music blaring from the loudspeakers, could have been out of the Shah Rukh Khan film. Only this time round, it was for real.

The hockey girls weren’t alone. The diminutive Mirabai Chanu, who lifted logs to start with—to make sure there was enough wood to light the fire in her village home 22 km from Imphal—ignited Indian hopes on the very first day of the competition in Tokyo. From failure in Rio to the silver in Tokyo, Chanu is proof that dreams do also come true with grit and hard work. Boxer Lovlina Borgohain’s village did not have a pucca road leading to her house, but the moment she was assured of a medal, the state government back home in Assam started construction in a gesture of appreciation for their new champion. While Chanu and Lovlina won medals, fencer C.A. Bhavani Devi, Manika Batra (table tennis), Kamalpreet Kaur (discus) have also impressed in Tokyo. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say women led from the front in these Games, and gave India more joy than their male counterparts.

A close analysis of the Indian effort, at the Games and more crucially in the preparatory run-up, will reveal that aspirations aside, brag-worthy performance is some distance away. We have taken some good steps, and made some progress too, but a place in, say, the Top 10 medal winners list at the Olympics is still at least a decade away. Tokyo was not an aberration. While we do expect shooting to pick up and perhaps boxing as well, do not expect a magical turnaround in Paris 2024. Our expectations need to be moderated: we can still aspire to a double-digit medal haul in Paris, but we are not on the threshold of breaking into the big league just yet.

This is not to doubt the talent or potential of Indian athletes. Nor to suggest that these men and women are not ready for the world stage. But it takes more than just talent to win at the Games. Take, for example, Saurabh Chaudhary in shooting. Over the past three years, Saurabh, 19, has won many medals in the 10m air pistol event. It was only natural to expect a medal from him in Tokyo. True to his billing, Saurabh scored an outstanding 586 (out of 600) in the qualifying round and made it to the final as the top-ranked shooter in a strong pool of 70. It looked like he had peaked at just the right time. But it all went awry for him in the first final relay of five shots. Saurabh totalled a poor 47.4 (on 50)—when he has never done a 47 in the past four years! That unexpected dip in performance came in an Olympic final.

Does that make Saurabh a bad shooter? Was he not ready for the big stage? No sooner than he had flubbed the 10m air pistol event, self-styled experts on social media were writing him off—he was all hype, no substance, they said. For some more parallel-universe context, even Novak Djokovic failed to win a medal at these highly unusual Games; Simone Biles chose to bow out of most of her gymnastics events citing mental health issues; Kento Momota crashed out; Ashleigh Barty made 55 unforced errors in the first round; and Naomi Osaka too failed to deliver. Saurabh Chaudhary is human—and still young.

Just two days after that setback, he was back at the range partnering Manu Bhaker in the 10m air pistol mixed event. This time, he was in stellar form. India scored 582 in the first qualifying round, an Olympic record, with Saurabh leading the charge with a spectacular 296 of 300. In the second qualifying round, where the top four teams make the cut, Saurabh finished with 194 of 200. Had Manu been even close to her best, Saurabh might have won a medal.

It’s this ‘what could have been’ feeling that defines India’s performance in Tokyo. What explains India’s seemingly chronic underperformance at the Olympics? Financial backing did improve considerably after Rio 2016. Shooters have had all the facilities they needed to excel. Yet, a confidential report by one of the coaches, sent to the National Rifle Association of India (NRAI) in 2018, says that more than 70 per cent of our shooters underperform at every major event. The report attributes this dip to pressure and the inability to self-regulate. It also notes that while we now have a lot of talent, we lack sports science. Manu Bhaker’s performance illustrates the point. In the rapidfire segment of the 25m pistol, Bhaker had a good 3 seconds to shoot a bullet. When she held her nerve, and utilised close to the allotted time, she ended up with scores of 10.7-10.9 (where only 10 is recorded); the only time she fired a shot in 1.7 seconds, she got an 8. She failed to make the final by 2 points.

There’s no questioning Bhaker’s talent; what she lacks is what Abhinav Bindra—still the lone Indian to win gold in an individual event—refers to as “the decisive 1 per cent”. After London 2012 (he won gold in Beijing 2008), Bindra modelled his entire training on sports science and came closest in Rio to winning his second Olympic medal. That’s what these young shooters need to do going forward: make use of sports science and learn to handle pressure. That may be easier said, but if done, Paris could be a different story for the current bunch of talented Indian shooters. Another coach said on condition of anonymity: “You ask why we win world cups but not Olympic medals. When they shoot at world cups, they know the next event is just a month away. ‘If not here, then at the next event’ is the thought process. But at the Olympics, they are not certain of a next chance four years down the line.” This now-or-never pressure at the Olympics, he says, is a big factor affecting performance.

“We have the 99 per cent but it is the battle for that 1 per cent that continues to trouble our sportspersons

– Abhinav Bindra, Olympic gold medallist, Shooting

Likewise with our archers and boxers. While Deepika Kumari and Atanu Das are both experienced campaigners, sports science is not a big feature of their training modules. A review of Deepika’s health parameters, monitored during the quarter-final against An San of Korea (the eventual winner), showed she was not in control of her nerves. She was trying too hard. Atanu Das, likewise, faltered in the final series against the Japanese after ousting a two-time Olympic champion, drawing attention to the inconsistency that continues to plague India’s archers.

The most crushing disappointment, however, was the tame, first-round exit of decorated boxers Vikas Krishan and Amit Panghal. Vikas, unconscionably, fought with a severe injury to his shoulder and never stood a chance. How could someone with a serious tendon injury even travel to Tokyo as a part of the Indian contingent? The Olympics are not a participation junket. While Vikas was injured, Amit, sources in the team confirmed, was fully fit and ready. What went wrong with him, then? Some say Amit hadn’t eaten right the night before, and apparently overate the next morning before heading to the venue—flyweight boxers need to watch their weight ahead of the bout. “Uska diet idhar-udhar ho gaya tha, woh sambhal nahin paya. Woh pehle round ke baad tired ho gaya (his diet went awry and he got tired at the end of the first round),” said one of the coaches. This kind of lapse is uncondonable at the highest level; competing athletes have to be monitored and managed professionally, with scientific aids at the ready. Santiago Nieva, the high-performance director for Indian boxing, made a startling revelation: “Amit had sparred with this Colombian player (Yuberjen Martinez) in Italy and we knew he was dangerous. Amit had to win it in two rounds, or it was going to be tough.” Nieva also confirmed that Amit was tired after the first round. How does this happen? How does one of India’s leading amateur pugilists lose steam after three minutes of boxing? Why bother with ‘high-performance coaches’ and pay them top dollar year after year if this is the quality of their intervention?

It seems some things in Indian sport will never change. While action is being taken against Manika Batra for refusing to have national coach Soumyadip Roy in her corner, we need to ask: why wasn’t Manika’s coach accredited? Had the TTFI (Table Tennis Federation of India) decided not to accredit general secretary M.P. Singh and helped Manika instead, the unnecessary controversy may have been avoided. “At IOA (Indian Olympic Association), we do not decide on the accreditations. We are like a post office—we accredited whoever TTFI suggested,” said IOA president Narinder Batra. This ‘babu culture’ persists in Indian Olympic sports, and Manika Batra’s fate is an illustration of its consequences.

The total medal count in Tokyo may be an improvement on Rio (where we got 1 silver and 1 bronze) but it’s nothing to crow about, certainly not for a country of 1.3 billion, with superpower aspirations. Should we expect a dramatic turnaround in Paris 2024? For perspective on how long it might take, the example of Great Britain may be apt. Britain had won a solitary gold medal in Atlanta in 1996. In 1997, National Lottery funds were ploughed into British Olympic sports, and in a decade and a half, Team GB had won 29 gold medals (London 2012). They added to their tally in Rio and at the time of going to press, Team GB was placed at #4 in the overall medal standings in Tokyo.

In India, the process has started. There is no question that Rio was a big disappointment, but it was also a reminder of the uncertainty of sport. You can train hard and prepare all you might—and yet falter on the big day. If there was a medal for preparation, Abhinav Bindra would surely have won it. Reassuringly for India, the building blocks of a revival are in sight. On the positive side of the ledger, funding for sport in India has increased. In 2016, the government of India was spending about Rs 11.5 per Indian on sport (Budget allocation: Rs 1,541 crore); by 2019, this had increased to Rs 16.5 per Indian (Budget outlay: Rs 2,217 crore).

The National Sports Development Fund was set up in 1998-99 with a measly corpus of Rs 2 crore. In two decades since, the Fund has garnered Rs 240 crore, with roughly 38 per cent of that amount coming from private sources, 35 per cent from government-owned companies and the rest from the government. Government funding of elite athletes, extended through the sports federations, for their training and participation in international events has gone up nearly fourfold between 2014-15 (Rs 130 crore) and 2019-20 (Budget ceiling: Rs 482.5 crore), the sports ministry reported in Parliament.

Under the government’s Target Olympic Podium Scheme (TOPS), which identifies elite athletes and supports their training, Rs 100 crore was earmarked specifically for Tokyo 2020, the Sports Authority of India had announced in December 2018. TOPS was set up in September 2014 and became operational in mid-2015. Abhinav Bindra headed its selection panel through 2017, when 220 athletes were funded by the scheme. In 2016, TOPS spent Rs 19.9 crore on athletes in 17 sports. This increased to Rs 28.2 crore across 19 sports in 2017-18.

National badminton coach Pullela Gopichand confirms the government has been supportive: “For the (SAI Gopichand National) Academy, they gave about Rs 5 crore from the NSDF (National Sports Development Fund). Also, about 50 players are supported in terms of their food and accommodation. So, food, accommodation plus tournament exposure for these 50 kids is huge support, which I get from the government of India.”

Add to this: private initiatives from the likes of Go Sports Foundation, JSW Sports and Olympic Gold Quest, and it’s clear the support infrastructure is slowly falling in place. For Britain, the turnaround was a 15-year cycle; India is barely four to five years into the process. We should hope to progress with every Olympics, and hope for much better in Paris 2024, but it’s probably more realistic to expect the big surge in India’s Olympic performance, the stuff every Indian dreams of, no sooner than Los Angeles 2028. Between now and that coveted glory lies a hard grind, a slow, barely perceptible march towards what Bindra calls “perfection on an imperfect day”.

Men Who Shone

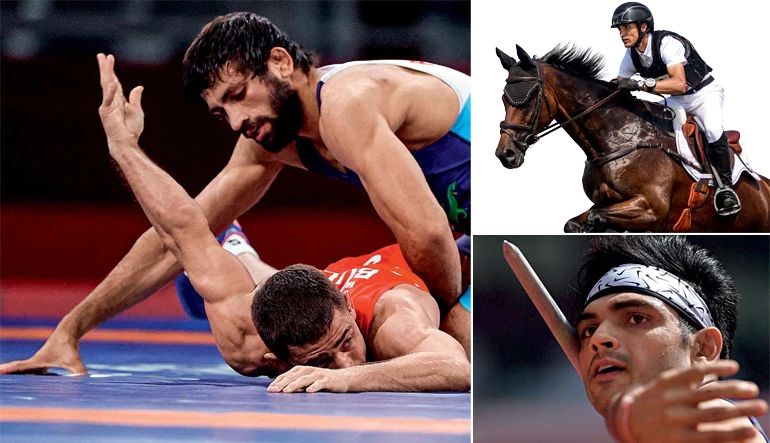

Though outperformed by India’s women athletes, the men also notched up some impressive records

NEERAJ CHOPRA 23 | Javelin Throw

The 2018 Asian Games gold medallist and former junior world champion lived up to his billing by finishing first in the qualification round, where he out-threw his biggest rival for the gold, Germany’s Johannes Vetter. In his very first throw, Chopra cruised past the qualification mark of 83.5m. Regardless of the result on Saturday, he made history by becoming the first Indian to qualify for the finals in this event.

RAVI KUMAR DAHIYA 23 | Freestyle Wrestling (57KG)

Dahiya became only the second wrestler after Sushil Kumar to make it to an Olympic final. After easing through two bouts on technical superiority, Dahiya demonstrated tremendous spirit and composure in the semis where he fought back with hardly a minute to go. Gold or silver, a new wrestling star is born.

FOUAAD MIRZA 29 | Equestrian (Eventing)

Competing with Seigneur Medicott, the horse with whom he won two silvers at the 2018 Asian Games, Mirza started out with a fine routine in dressage which saw him finish in the top 10. His ranking dropped in the subsequent rounds—cross country and jumping—but the world #70 rider rode with aplomb to qualify for the final round of 25 pairings. It was an incredible feat among an elite group of 63 riders from across the world.

Under Performers

Hope rode high for India’s archers, shooters and boxers, but it was not to be. Lacklustre performances led to early exits

ARCHERY

Deepika Kumari arrived in Tokyo ranked world #1, but only made it as far as the quarter finals—her best showing in three Olympics—where she fell to the eventual Olympic champion, South Korea’s An San. Atanu Das beat 2012 Olympic champion Oh Jin-hyek in a thrilling contest, but then lost to Tokyo’s bronze medallist Takaharu Furukawa in the pre-quarters. The favoured mixed team pairing of Kumari and Das didn’t materialise after Pravin Jadhav outscored Das in the individual ranking round.

SHOOTING

Many hoped India’s shooters would match, if not improve, the London 2012 performance, where India’s contingent won two medals. It wasn’t to be, with only Saurabh Chaudhary making it as far as the finals. The rest buckled under pressure, with many, including Manu Bhaker and Abhishek Verma, failing to hit the target at the tail end of the competition.

Shooters had all the facilities to excel. Yet a confidential report sent to the NRAI said 70% shooters underperform at every major event due to pressure or the inability to self-regulate

MEN’S BOXING

Expectations were high for India’s male boxing contingent, riding on a squad that included flyweight world #1 Amit Panghal. Instead, Panghal, along with Manish Kaushik and Vikas Krishan, was comprehensively beaten in the first round itself. Satish Kumar was the lone warrior to win a match. With this result, Vijender Singh in the 2008 Beijing Games is still the only male Indian pugilist to win an Olympic medal.

Grit & Glory

India’s women athletes persevered against heavy odds to leave their mark on the world stage

LOVLINA BORGOHAIN 23 | BOXING

“There was this belief that my parents must have done something bad in their past lives to have deserved three daughters,” said Borgohain, recalling the taunts her parents faced in Bara Mukhia village in Assam’s Golaghat district. That all three took to a combat sport like muay thai didn’t help. While her twin sisters gave it up, Lovlina persisted, later switching to boxing. Now, all anyone can talk about is her Olympic medal and how it has transformed the village. Her bronze medal has paved the way for a concrete road to ensure her smooth homecoming.

RANI RAMPAL 26 | HOCKEY

Growing up in a tiny one-room house in Shahbad, Haryana, Rampal knew early on that picking up the stick could be a way out for her family which was struggling to manage two meals a day. At 15, she became the youngest player to make it to the national team and was immediately nominated for FIH’s 2010 Young Player of the Year Award. A veteran at just 26, Rampal has led India in back-to-back Olympics now. A year after the Rio Games, she realised another dream—buying her family a house.

KAMALPREET KAUR 25 | DISCUS

For Kaur, taking up a sport meant avoiding the pressure of early marriage that many young girls in her village Kabarwala in Punjab face. “I thought sports will be my ticket to get a job and avoid marriage,” she told the website Scroll in an interview early this year. Luckily, the strappy 6’1” girl had her father Kuldeep Singh’s support. But Kaur didn’t want to burden him financially, given that the joint family lived on modest earnings earned through farming. So Kaur moved to the Sports Authority Centre in Badal to pursue shot put before turning to discus throw on the recommendation of coach Preethpal Maru. Kaur showed immediate results at the youth level, breaking the under-20 national record. The funds shortage, though, remained till she got a job in the Railways and was selected to be part of Go Sports Foundation’s Rahul Dravid Athlete Mentorship Programme. Kaur’s sixth place finish in the finals of the Tokyo Games matches Krishna Poonia’s feat in 2012 London.

MIRABAI CHANU 26 | WEIGHTLIFTING

In her childhood, lifting weights was more a necessity than an Olympic dream for Mirabai Chanu. Youngest of six siblings, she would carry firewood on her head, at times a heavier load than her two brothers, so as to reduce the burden on her mother, who worked in the paddy field in addition to running a small tea kiosk in Nongpok Kakching village in Manipur. The family, after all, couldn’t depend only on her father’s salary as a construction worker in the Manipur public works department. When Mirabai, then 12, decided to take up weightlifting and travel daily to the Khuman Lampak stadium in Imphal for practise, the family chipped in with all its resources. Her sisters saved and contributed for her commute while on occasion the youngster walked half the distance so as not to inconvenience the family. All those hardships paid off after Chanu started faring well internationally, especially in 2017, when she became only the second Indian to become a world champion. The silver at Tokyo has already reaped rich dividends, with the Manipur government and her employers, the Indian Railways, announcing cash awards. The weight of supporting her family already seems lighter.

.