On August 23, Bihar chief minister and Janata Dal (united) leader Nitish Kumar formed an unlikely alliance with his political rival, the Rashtriya Janata Dal’s Tejashwi Yadav, who also happens to be the leader of the opposition in the state assembly. The two of them, along with the leaders of 10 other parties from Bihar, met Prime Minister Narendra Modi in New Delhi and demanded a caste-based census, even though the Union government had in July stated in Parliament that an enumeration of castes will not be part of the 2021 census “as a matter of policy”.

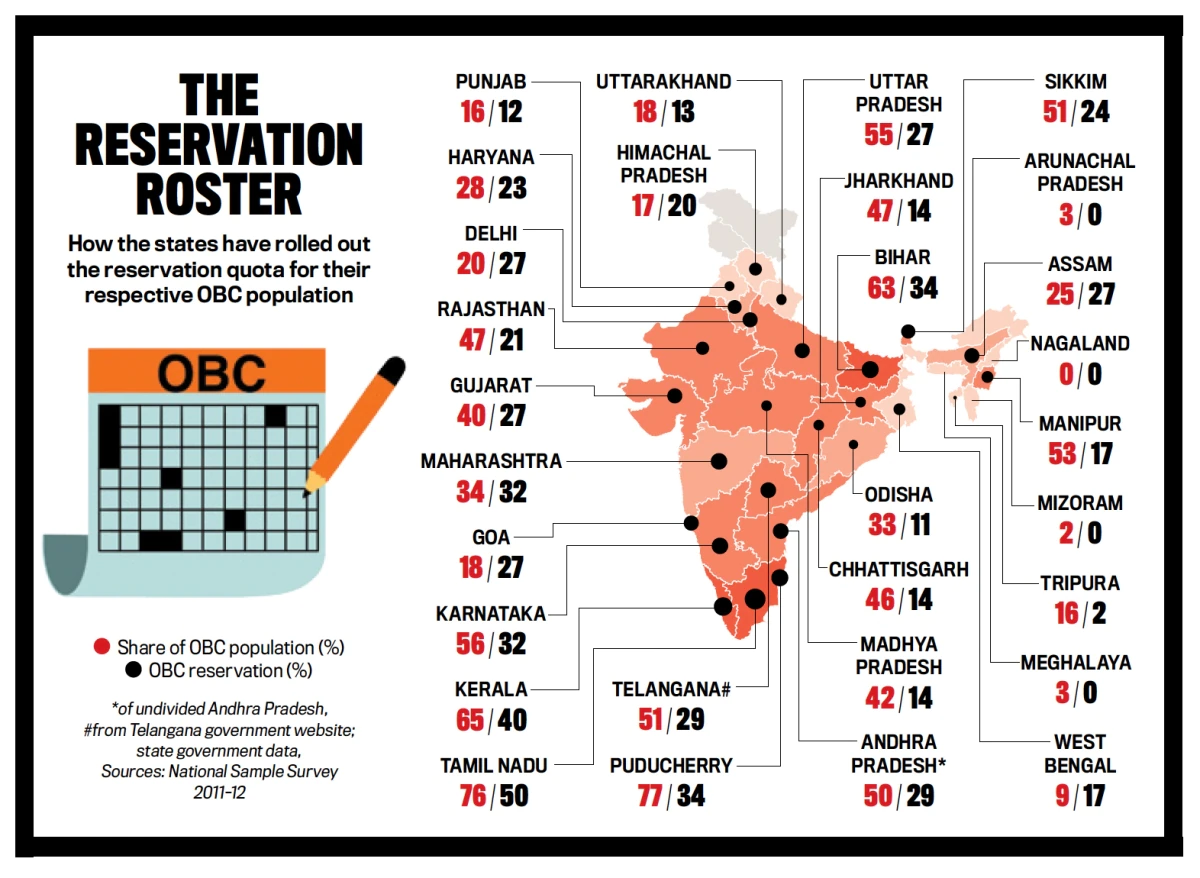

At the core of this growing clamour for a caste census is the desire to pinpoint the strength of the OBCs (Other Backward Classes), who have of late emerged as the most influential voting group in electoral politics. With no official count, there is a perception that the OBCs account for more than 52 per cent of the population (the Mandal Commission estimate from four decades ago, which took as its base the 1931 caste census, the last time it was done), and, therefore, deserve more than 27 per cent reservation. If a caste census substantiates this notion, this may result in a much stronger demand for a rejig of the existing reservation structure. (Timeline: Genesis of the caste census)

At stake will be more than 9 million government jobs—both at the Centre and in the states—across India, and admissions in educational institutes, including 2.3 million engineering seats and more than 80,000 medical seats. Fearing a backlash from other caste groups, particularly the upper castes, the BJP-led Union government is unwilling to disturb the status quo. This is especially so as Uttar Pradesh goes to assembly election in less than six months, and where the BJP is looking for a second term.

This is the reason why Prime Minister Narendra Modi, an OBC himself, has taken a U-turn from what his cabinet colleague Rajnath Singh had promised in 2018—that data on the OBCs will be collected in the 2021 census. Meanwhile, the other political parties are seeking to use this demand to not only woo the OBCs but also rob the BJP of some of the most crucial weaponry in its electoral arsenal.

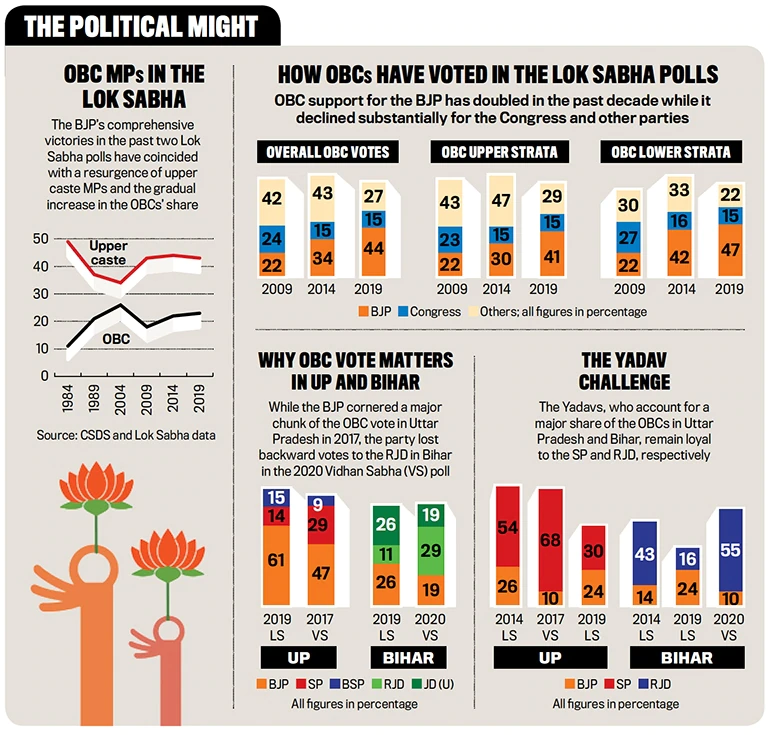

A 2019 post-poll study by the Delhi-based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) found that the percentage of OBCs voting for the BJP doubled from 22 per cent in 2009 to 44 per cent in 2019. In the 2017 UP assembly election, when the BJP won 312 seats in the 403-member house, its OBC vote share was 47 per cent. Currently, 32 per cent of its legislators in the state are OBCs, up from 20 per cent 10 years ago.

However, the other parties are eager to challenge the BJP in vying for the OBC vote. The demand for a caste census has come not just from Bihar’s leaders, but from almost all non-BJP political parties, including the Congress, NCP (Nationalist Congress Party), BJD (Biju Janata Dal), DMK (Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam), SP (Samajwadi Party) and BSP (Bahujan Samaj Party). The saffron party’s refusal has given Opposition parties fresh ammunition to target the Modi government, and particularly the Yogi Adityanath government in UP. The Samajwadis and the Congress have started organising OBC sammelans, while the BSP is also creating a din. “We have always said that the OBCs must get their due, and for that to happen, they must know their share in the population. The BJP doesn’t have the welfare of the OBCs at heart,” says BSP MP Ram Shiromani Verma, a member of the parliamentary joint committee on the welfare of Other Backward Classes.

A further cause of embarrassment for the NDA government is that allies such as JD(U) and Apna Dal have joined the chorus too. Even the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC) has endorsed the idea. “The commission’s view is that there should be an OBC census. It’s for the government to act now,” says its chairman Dr Bhagwan Lal Sahni. Then, there are the intra-party contradictions. In the Lok Sabha, party MP Sanghmitra Maurya has raised the demand, while Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan, an OBC leader himself, termed the caste-based census “a revolutionary process”.

With its back to the wall, the BJP now says the party is not opposed to the idea “in principle” but wants “broader consensus” on the issue. “PM Modi has been considering the matter seriously,” says BJP MP Rajesh Verma, chairman of the OBC parliamentary joint committee. “We have not rejected the idea, but there has to be an informed debate on the matter in Parliament first.”

Bihar CM Nitish Kumar with other state leaders after meeting PM Modi on the caste census issue; (Photo: Chandradeep Kumar)

Why the sudden demand for a caste count

The surge in demand for a caste census was triggered by a March 4 Supreme Court verdict which quashed the 27 per cent OBC quota in local bodies in Maharashtra for want of empirical data on the backwardness of the communities. The 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments provided for reservations for backward class and women in panchayat raj institutions. The Supreme Court verdict scrapping OBC reservation is applicable to all the states. “The states want a caste census because 900,000 OBC representatives could lose their posts in the country, including 56,000 in Maharashtra alone,” says author and OBC activist Professor Hari Narke, head of the Mahatma Phule Chair at the University of Pune.

In India, while the census includes the numbers of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, ‘general’—primarily the upper—castes, and OBCs are not enumerated. The SCs/ STs have been given reservation in government jobs and educational institutes proportionate to their share in the population—15 per cent and 7.5 per cent, respectively.

However, the government cannot arbitrarily increase the share of OBC reservation due to a legal roadblock. In 1992, the Supreme Court ruled that caste-based reservation in jobs cannot exceed 50 per cent. Since SCs/ STs corner 23 per cent, there is little scope for any hike in the OBC share. As a caste census can provide empirical data, the demand for it gained a new currency; the electoral intent was a bonus. “The majority of the political spectrum, including BJP MPs and allies of the party, have supported, and demanded, a caste census. The sooner a comprehensive exercise is done, the better,” says Abhishek Manu Singhvi, Rajya Sabha MP, Congress.

The sudden desperation to take up the OBC cause is due to their electoral significance. In the past three decades, the community—or its elements—have been the backbone of caste-based parties such as the SP, RJD and JD(U), and also the key differentiator in the swinging electoral fortunes of the two national parties—the BJP and Congress. Nowhere was this more evident than in the grand display of unity in Parliament. In the just-concluded monsoon session, the opposition did not participate in any debate against the alleged Pegasus snooping case involving the government. But when the 127th amendment to the Constitution Act—reinstating the power of the states to declare any caste group as OBC—came up, all the parties not only took part in the debate but also voted unanimously in the bill’s favour.

The BJP’s reluctance to do an OBC census

Several political analysts point out that a caste census poses a significant dilemma for the BJP and its traditional caste calculus. While Dattatreya Hosabale, general secretary of the BJP’s alma mater RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), reiterated in August that the Sangh strongly supports reservation, the organisation has refrained from saying anything about the caste census. In 2011, Hosabale’s predecessor Suresh Bhaiyyaji Joshi had offered an insight into the RSS’s thoughts on the subject when he said that a caste-based census was against the idea of the casteless society envisaged by leaders such as Babasaheb Ambedkar.

“The states want a caste census because, after the SC verdict, 900,000 OBC representatives could lose their posts across the country, 56,000 in Maharashtra alone”

– Prof. Hari Narke, Head, Mahatma Phule Chair, University of Pune

Of course, there’s more to it. The BJP emerged first as a party of the Brahmins and Baniyas, two upper caste groups. However, the upper caste vote alone was insufficient to sustain its electoral ascent, especially after the OBCs acquired a distinct political identity following V.P. Singh’s implementation of the Mandal Commission report. To counter the ‘Mandal politics’, the party broadened its political base by focusing on a ‘Hindutva’ identity—an amalgamation of all Hindu identities, irrespective of caste. This was the reason why the BJP—which had passed a resolution in its Bhopal national executive in 1985 demanding the implementation of the Mandal Commission report but later changed tack and withdrew support to the V.P. Singh government over the Mandal issue—stepped up the Ayodhya Ram temple agitation, for it helped bring the OBCs and Dalits under an umbrella Hindu identity.

Political observers believe that the BJP fears a caste census will split the Hindu vote. The move may help consolidate its support base among the OBCs, but it could also invite a backlash from the upper castes. “If we have actual data, the regional caste-based parties may raise the demand to lift the 27 per cent cap on OBC reservation,” says Sanjay Kumar, director, CSDS.

Any demand to rejig the reservation structure may lead to a repeat of the social unrest and upper caste dissension that accompanied the implementation of the Mandal reservation system. And the BJP can ill afford to offend its core upper caste voter base. “The BJP does not have the cushion of minority votes,” says a BJP leader in Patna. “We may earn some brownie points with the OBCs, but the regional parties will be the real gainers. The risk-reward ratio is skewed against us.”

“Any government would be worried about upsetting the upper castes. though it claims to champion the cause of the OBCs, the BJP finally a party of the upper castes. so, the worry is more”

– Sudha Pai, social scientist

In fact, even as it has wooed the OBCs, the BJP has been careful not to hurt the interests of the upper castes. In 2019, the Modi government introduced 10 per cent reservation for the economically weaker sections (EWS) of socially advanced groups, or the upper castes. “Any government would be worried about upsetting the upper castes. Though it claims to champion the cause of OBCs, the BJP finally is a party of the upper castes. So, the worry is more,” says social scientist Sudha Pai.

Other experts disagree with the analysis that the BJP fears an upper caste backlash. “There is a lot of conflict and violence around religion, but it’s people of one religion that are being counted. Counting doesn’t lead to conflict. Conflict is engineered by groups with a polarising agenda,” says Ashwini Deshpande, director of the Centre for Economic Data and Analysis at Ashoka University in Haryana. Prashant K. Trivedi, an associate professor at the Giri Institute of Development Studies in Lucknow, sees a vast change in the socioeconomic scenario of the country in the past three decades with the opening up of lucrative corporate jobs “seriously altering the earlier status of government jobs as a do or die thing”.

However, the reluctance to conduct a caste count has to do with other fears as well. Several dominant caste groups, such as the Patidars in Gujarat, the Marathas in Maharashtra and the Jats in Haryana have been agitating, often violently, demanding OBC status. Any count without resolving these contentious demands may create a bigger mess for the Centre. There is also no clarity on the official classification of some caste groups. For instance, the Jats enjoy OBC status in Rajasthan but not in Haryana or in the central list. In several states, including Karnataka, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, even Brahmins have found a place in OBC lists. “There are logistical issues which need to be resolved first. Otherwise, it will end up being a flawed exercise like the 2011 Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC),” says K. Laxman, national president of the BJP’s OBC wing.

J.K. Bajaj, director of the Centre for Policy Studies in Chennai and member of the Justice Rohini Commission on the sub-categorisation of OBCs, agrees that the SECC had anomalies but attributes it to the enumerators not having a list of castes. “Karnataka, in recent years, carried out a state-level caste census based on a comprehensive list of all castes before the actual enumeration,” says Bajaj. He cautions that this could be a time-consuming exercise and may not be possible in the current census which has already been delayed because of the Covid pandemic.

The BJP leaders are now cleverly seeking to put the ball in the state governments’ court. Ganesh Singh, a BJP MP and former chairman of the parliamentary committee on welfare of Other Backward Classes, says that whether the Centre counts the OBCs or not, “the states must start the exercise on their own”. The BJP anticipates that no state will take the bait as the outcome may seriously disturb the political and social equilibrium. The Siddaramaiah-led Congress government in Karnataka had conducted a ‘Socio-Economic and Education Survey’ in 2015 in which caste was also demarcated but successive Congress and BJP governments have not published its results. Leaked findings estimated that the population of the Lingayats, one of the most dominant caste groups in the state, was below 10 per cent (contrary to claims of them being 18 per cent). Representative bodies of the Lingayats and Vokkaligas, the two dominant caste groups, had even threatened protests if the findings were made public. The BJP expects that states will refrain from such an exercise for fear of being forced to recalibrate the reservation pie. For instance, Karnataka offers 32 per cent reservation to the OBCs. The 2015 caste count reportedly found that SCs accounted for 24 per cent of the population, making them the single biggest group. This may make them demand more than the 15 per cent quota of reservation to make it proportionate to their share of the total population. With STs cornering 3 per cent of the pie, the state government cannot increase SC reservation without violating the 50 per cent cap.

Does India need a caste census?

Most experts agree that there is no harm in undertaking a caste census since caste identities are a reality of India’s sociopolitical existence. “When a category called OBC has been created constitutionally, why should there be a debate on the question of counting this group?” asks Professor Narender Kumar of the Centre for Political Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi.

The BJP’s rivals argue that a caste count will help the government frame better policies and welfare programmes for these groups. “The caste census is not just about finding the quantum of backward castes,” says Manoj K. Jha, an RJD Rajya Sabha MP and professor at the Delhi School of Social Work. “It’s about holding up a mirror to the status of a large section of people on the socioeconomic ladder. For policymaking and social equilibrium in a welfare state like India, a census is mandatory.” A top JD(U) leader says the party believes a caste census will help the state identify those sections in the OBC still outside the social welfare radar.

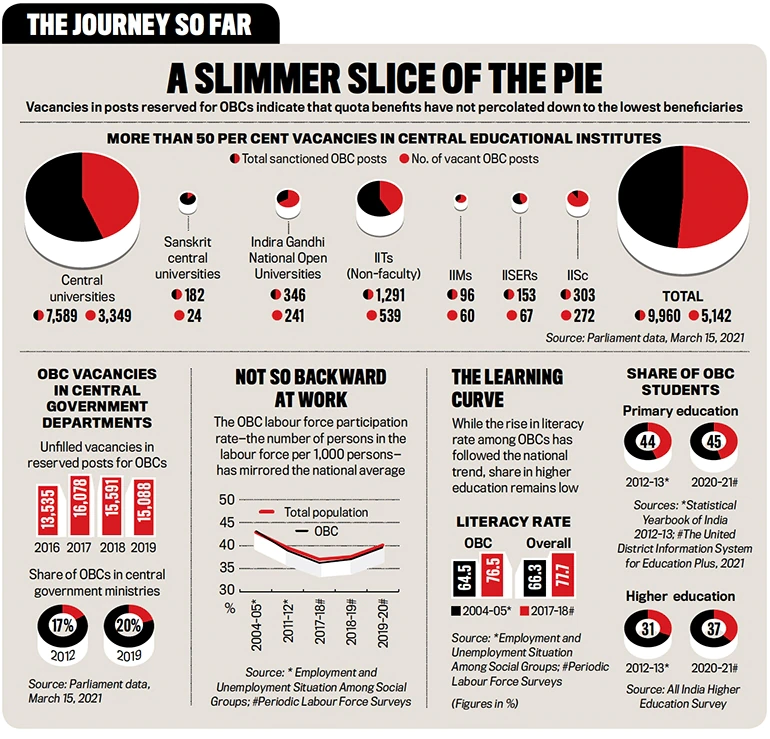

According to data revealed in Parliament, around 21 per cent of the workforce in the central ministries and public sector enterprises is from among the OBCs (27 per cent is earmarked for them). While the OBCs account for 45 per cent of the students in primary education, their share drops to 37 per cent in higher education. The BJP’s Laxman argues that instead of a headcount, states need to be pushed into effectively implementing reservation. Of the 15,000 notified OBC communities, 9,500-odd don’t even get its benefits. Narke says the government needs to spend more on the socioeconomic uplift of OBCs, for which their enumeration is a must. “In this year’s budget, the Centre allocated just Rs 18 per OBC person for the entire financial year,” he claims. Ganesh Singh accepts that lack of data has hindered a focused approach on OBC children. “That’s why I suggested a separate fund for the OBCs,” he claims.

How the BJP is negotiating the maze

While the Centre has ducked a response, the BJP has already launched an offensive against the opposition parties. Following the March 4 apex court verdict, the saffron party launched a statewide agitation against the Uddhav Thackeray-led MVA (Maharashtra Vikas Aghadi) government in Maharashtra, alleging that it had failed to protect reservation for OBCs in local bodies. It also announced that if reservation was not restored, it would field only OBC candidates for the upcoming local body election. The Thackeray government responded by seeking the 2011 SECC data on OBCs from the Modi government so that it could submit the same as empirical evidence in court. Ironically, the previous Devendra Fadnavis-led BJP-Shiv Sena government had also made a similar appeal to the Centre, only to be rebuffed.

Apart from the counter-strike, the BJP is also focused on getting the optics right. The share of OBC members in Modi’s council of ministers has jumped from 13 in May 2019 to 27 now. Ensuring that voters take note of this, it even organised an event in Delhi to felicitate the 27 ministers. After the 127th Constitution Amendment Act was passed, the BJP announced plans to hold 70 ‘Modi samarthan sammelans’ across the country to showcase, among other things, the Centre’s actions to empower the OBCs.

In July, the Centre announced 27 per cent reservation for OBC students in medical and dental courses under the all-India quota. The income limit for the creamy layer among the OBCs has also been raised, from Rs 6 lakh to Rs 8 lakh (which could go up to even Rs 16 lakh, as recommended by the NCBC). The NCBC itself got constitutional status under the Modi regime. Simultaneously, the BJP continues to work to dismantle the monopoly of caste-based parties over OBC votes. The party has mobilised support among the marginalised OBCs in various states by floating a narrative that regional parties help only the dominant OBC castes, who corner all the benefits. “The dominant OBC castes in every state are inclined to support a particular party, such as the Yadavs favouring the RJD in Bihar and SP in Uttar Pradesh, Lingayats backing the JD(S) in Karnataka and Kurmis voting for the JD(U) in Bihar. While these parties are focused on their core support caste, the BJP has intelligently sought to mobilise the other OBC castes which did not get commensurate reservation benefits,” says Prof. Kumar of CSDS. The BJP campaign against the Yadavs worked in UP as the party cornered the biggest slice of the non-Yadav OBC votes in the previous two Lok Sabha elections and the 2017 assembly election. The BJP’s alliance with non-Yadav OBC parties such as the Kurmi-dominated Apna Dal, the Rajbhar-dominated SBSP and the Nishad Party has also worked.

Ex-CM Kamal Nath and other Congress leaders at a protest on the OBC reservation issue in Bhopal, Aug. 10; (ANI photo)

Critics believe that the Modi government may now utilise the Rohini Commission report to consolidate its base among non-dominant OBC castes. Constituted in 2017, the four-member commission headed by retired Delhi High Court chief justice G. Rohini has examined how the 27 per cent reservation for OBCs is being implemented. According to sources, the commission found that of the close to 6,000 castes and communities among the OBCs, a mere 40 had seized 50 per cent of the quota for admission in central educational institutions and recruitment to civil services. Just 10 castes have monopolised a quarter of the 27 per cent OBC quota. Nearly 20 per cent of OBC communities have not got quota benefit from 2014 to 2018. The committee is likely to recommend splitting the 2,633 OBC sub-castes in the central OBC list into four groups for equitable distribution of the reservation pie.

Experts have been sceptical about this exercise, especially in the absence of a caste count. “The government-appointed commission talks about sub-categorisation, but how will we know there is equitable distribution unless we have data by jati?” asks Prof. Deshpande. Yet, the subcategorisation of OBC castes is not a new concept. Already 11 states—West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Bihar, J&K, Haryana and Puducherry—have it. The sub-categorisation of Dalits, identifying a number of ignored Dalit castes as Mahadalits, has paid rich dividends to Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar in the past. To replicate such an experiment, Adityanath appointed a social justice committee in May 2018 to rationalise the OBC reservation structure in UP. His government is yet to implement the recommendation of the committee—splitting the OBC bloc into three sections—backward class, more backward and most backward class—but the dilly-dallying, coupled with the refusal to conduct a caste census, has cost the BJP some allies, namely the SBSP and the Maurya community-dominated Mahan Dal, who are now cosying up to the SP.

What’s the way out?

While the BJP must quickly find a new formula to crack the political puzzle around OBCs, most social scientists agree that the real solution to the problem lies in a dispassionate review of the reservation policy. “Reservation is not a magic wand that can eliminate caste inequality. Many more policies need to be put in place to achieve caste equality. Reservation is only a small part of the overall policy mix,” says Prof. Deshpande of Ashoka University. Trivedi of the Giri Institute of Development Studies prescribes thorough land reforms as a critical measure for the backward classes. “The rescuing of the agriculture economy from the ensuing crisis would be a major step,” he says.

“The caste census is not just about the number of OBCs, it’s about holding up a mirror to the status of a large section of people on the socioeconomic ladder”

– Manoj K. Jha, RJD Rajya Sabha MP and Professor, Delhi School of Social Work

Others call for a review of the Mandal Commission’s criteria for identifying backward classes. Sociologists such as Dipankar Gupta have argued that the Mandal Commission’s “flawed” system of weightage allowed several undeserving communities a place in the OBC category. Social scientists Satish Deshpande and Yogendra Yadav have suggested that not just caste but several other indicators, such as community, gender, family background (managerial, professional, clerical, non-income tax-paying) and type of schooling (government or private, English or vernacular medium) should also be considered.

The other big concern is the absence of a timeline for reservations. The Constitution had proposed that the SC/ ST reservation policy be valid for a decade and subsequently be reviewed in terms of the progress made. But rather than an extension based on an in-depth review, it has been renewed every decade as a matter of course because it is a political hot potato. Apart from fixing a firm timeline for reservations, many experts argue that other indicators, including income, rather than castes, should be made the criteria to determine reservations for the underprivileged. “A caste census will make no sense if the count doesn’t do cross-tabulation in terms of income, education level and land ownership among OBCs,” says social scientist Sudha Pai. Will the government bite the bullet?

– with Amitabh Srivastava and Anilesh S. Mahajan

.