BJP state president C.R. Patil is ambitious. He is on a mission to surpass the Congress’s 1985 record, when the party under Madhavsinh Solanki won 149 out of 182 seats. No party has touched this magic number since—not even under the almost decade and a half of Narendra Modi’s rule as chief minister. But the BJP did achieve its highest tally so far under Modi—127 seats in 2002. For Patil and the BJP, Gujarat is a must-win battle as the PM’s reputation is at stake. Patil is working on all fronts to ensure success, even willing to deviate from his earlier stand that nobody from the Congress would be inducted in the BJP. Among those he won over from the Congress is Jayraj Singh Parmar, a former spokesperson for the party, who joined the BJP in February and can influence 4-5 assembly constituencies in Mehsana district of north Gujarat. Many more defectors are likely to be welcomed.

Graphics: Tanmoy Chakraborty

Apart from these moves, Patil is relying on the BJP’s strong organisational network to beat anti-incumbency. Pradeepsinh Vaghela, the 41-year-old BJP general secretary, keeps tabs on the support base, sitting in the party headquarters in Gandhinagar. He says the ‘panna pramukh (page committee)’ system has been a robust mechanism to consolidate supporters. Each page of the voters’ list has 30 names, and a committee of five party workers is supposed to monitor them. “We have a target of appointing 71 lakh page committee members. At present, we have 62 lakh,” says Vaghela, a firebrand next generation leader. “We will have 35 lakh active workers encouraging voters to vote for BJP.” The party has also made a list of ‘kriyasheel karyakarta (active workers)’—those who have added at least 100 new members—and given them smart ID cards so that the leaders can be immediately updated when they add more members.

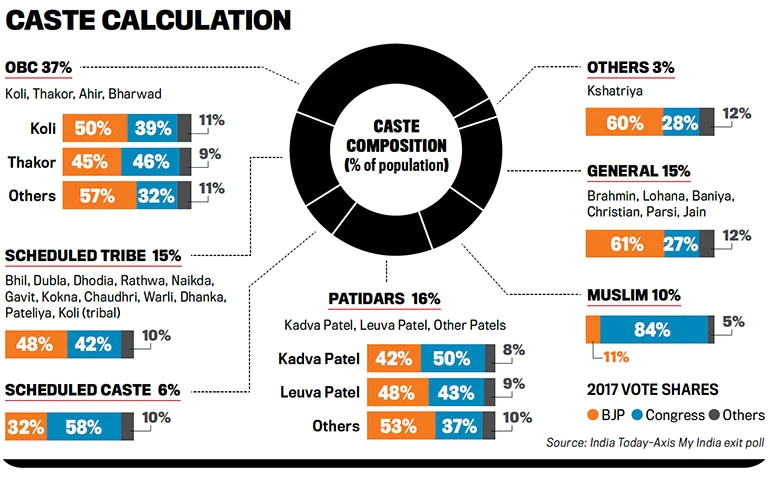

Caste dynamics also favour the BJP. While the prime minister remains its biggest magnet for all communities, the party also has a battery of leaders from both sections of the Patidar community—Kadva Patels and Leuva Patels. While CM Bhupendra Patel is a Kadva Patel, Union health minister Mansukh Mandaviya is a Leuva Patel. The party also has a sizeable presence among the OBCs (other backward classes)—Kolis and Thakors—while upper-caste Hindus have been loyal BJP voters for more than three decades.

To dodge anti-incumbency, the BJP had replaced the entire cabinet under Vijay Rupani with new ministers led by Bhupendra Patel in September 2021. Now, the government is looking to win over voters with a thrust on the Mukhyamantri Amrutum Yojana, its mass health insurance scheme, and by providing tapped water to every household. It expects to achieve the target of 100 per cent tapped water supply by September. “We have completed 93 per cent work. The rest will be done soon,” says a senior official from the CM’s office.

However, the CM’s low public profile and rising inflation may hamper the BJP’s prospects. “Even after eight months, many people do not know who the CM is,” says a senior BJP leader. “Humble and modest, he likes to stay away from the public glare, but the time has come to be vocal.”

Meanwhile, rising prices of fuel, gas and electricity have shaken the middle class, the BJP’s core voter base. Ahmedabad resident Mitul Patel complains that his electricity bill for two months was a whopping Rs 18,000. “I use two air conditioners in my house, but this power bill is unprecedented,” he says. The prices of piped gas and CNG, too, have gone up. “Commuters have started complaining as we had to hike the fare for shared rickshaws from Rs 15 to Rs 25,” says Shailesh Prajapati, an autorickshaw driver.

AAP’s rise may have enlivened Gujarat’s political atmosphere, but it has nobody to swing votes of any caste group

Many in the BJP believe that Saurashtra-Kutch is the party’s Achilles’ heel. In 2017, the Patidar agitation damaged its prospects in this region, where it won just 23 of 54 seats. With Leuva Patels in a majority here, the BJP is trying to induct influential community leader Naresh Patel to woo them. “His clout will remain until the polls at least,” says a BJP leader. “Even if people later start looking at him as a politician and not a social worker, he would have served our purpose.” The BJP might offer him the post of deputy CM.

Interestingly, leaders who broke away from the BJP ended up helping the party’s cause in three successive elections—2007, 2012 and 2017—by ensuring anti-BJP votes didn’t go to its main rival. In 2007, Gordhan Zadafia, a minister in then CM Modi’s cabinet, got most of the anti-BJP votes for his Gujarat Parivartan Party (GPP) instead of the Congress getting them. Former CMs Keshubhai Patel (GPP) and Shankersinh Vaghela (Jan Vikalp Morcha) did the trick for the BJP in 2012 and 2017, respectively. In 2017, NOTA votes exceeded the winning margin in some seats. Had the 551,615 NOTA voters pressed the button for the Congress instead, the BJP would have been sitting in the Opposition.

The Congress Offensive

The mood at Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan, the Congress headquarters in Ahmedabad, was upbeat on April 6. Party workers looked happy after returning from Sabarmati Ashram, where they had launched the ‘Azadi Gaurav Yatra’. Aimed at mobilising Congress workers of Gujarat and Rajasthan, the yatra will cover four districts of north Gujarat—Ahmedabad, Gandhinagar, Mehsana and Banaskantha—before turning towards Delhi, where it will culminate on June 2.

The yatra was initiated after the state Congress appointed 76 general secretaries, the highest number so far, to take on the BJP. But even as the workers reached the party office on April 6, news filtered in that around 400 Congress workers from Banaskantha had joined the BJP earlier in the day. “The BJP is poaching Congress workers because, contrary to the perception, that it is inactive, our party is alive in the state. We have a team. There is strong anti-incumbency and the government is corrupt,” claims Manish Doshi, chief spokesperson of the Congress.

While addressing party workers in March, former party president Rahul Gandhi had insisted on making pragmatic promises. “We have a bright future in Gujarat. Don’t promise people the moon if you can’t get them the moon,” he advised. He also asked them to put their heart into the fight against the BJP. “You can’t win if you are mentally defeated,” he is reported to have said.

Acting on his advice, the Congress is focusing on the tribal areas, which it believes could be a game-changer this time. Anant Patel, its MLA from Vansda, mobilised tribals against the Centre’s project to link the Par, Tapi and Narmada rivers. Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman had announced the Par-Tapi-Narmada linking project in her budget speech in February. The project was to transfer river water from the surplus regions of the Western Ghats to the deficit regions of Saurashtra and Kutch. The Par originates from Nashik in Maharashtra and flows through Valsad, Gujarat; the Tapi originates in the Satpura range and runs through Maharashtra and Surat; the Narmada originates in MP and flows through Maharashtra and Gujarat’s Bharuch and Narmada districts.

Tapping into the tribals’ fears that the river-linking project will displace them, Anant Patel led protests in several places in east Gujarat. On April 5, state BJP president Patil announced that the Centre has decided to stall the project in the absence of consent from the governments of Gujarat and Maharashtra. This has come as a shot in the arm for the Congress.

Both BJP and Congress are trying to induct Naresh Patel, a Leuva Patel community leader; (Photo: Nandan Dave)

Strong support from its core voters—Muslims and tribals—has been the Congress’s strength, and the party has been alleging that the BJP has invited the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) to Gujarat to cut into that base. According to political observer Shirish Kashikar, Asaduddin Owaisi’s AIMIM (All-India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen) is another headache for the Congress as it has been weaning away its traditional Muslim votes.

A bigger problem, however, is the lack of a dynamic and inclusive leader. State president Jagdish Thakor is known as a good organiser, but lacks wide acceptability. The working president Hardik Patel—the face of the Patidar reservation agitation—seems to have lost his appeal after joining the Congress in 2017. “One can be a hero for only one cause. People won’t accept you as a hero for every single cause,” says a senior Congress leader.

The party hopes to do better in Saurashtra and south Gujarat. Like the BJP, the Congress, too, is trying to rope in Naresh Patel. As chairman of the Shri Khodaldham Trust, the biggest organisation of Leuva Patels, he has much influence over the community in 30-35 assembly constituencies. The trust manages the temple of Goddess Khodiyar, the community’s patron deity, in Rajkot. As the Congress has been unable to attract upper-caste Hindus since 1990, Naresh Patel would be a prize catch. However, a section in the party believes his entry would alienate the OBCs as they don’t get along with the Patidars. They are also sceptical on whether Hardik, a Kadva Patel, will accept Naresh.

AAP Makes Inroads

AAP, which has set its sights on Gujarat after its Punjab victory, cashed in on a chance to expose the chinks in the BJP-ruled state’s education system. It all started with the national BJP social media team tweeting a caricature of AAP convenor and Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, criticising him for his handling of protests by schoolteachers in the national capital. On April 6, Gujarat education minister Jitu Vaghani asked those who do not like the schools in the state to go to whichever state or country they like. Delhi education minister Manish Sisodia retaliated the next day, saying the BJP has failed to improve the education system in Gujarat after 27 years of ruling the state. “People need not leave Gujarat. They will bring AAP to power and a glorious education system like in Delhi will be provided to them,” he tweeted.

The BJP had chosen the wrong time to take on AAP over school education. After all, around 600 government schools—each of which had less than 20 students on its rolls—have been shut down in the past year in Gujarat, especially in tribal areas. The state has also seen protests by parents against high school fees. Clearly, Vaghani had been caught on the wrong foot and his party’s top leaders eventually asked him to refrain from making unnecessary statements on education. But then the damage had been done by then.

As for AAP, its rise seems to have enlivened Gujarat’s political landscape. The party completed its statewide ‘Tiranga Yatra’ in the first week of April. It organised rallies in each of the 182 assembly constituencies. AAP’s Gujarat president Gopal Italia claims his party has at least 100 active workers in each constituency. Next in line is ‘Jan Samvad’, the party’s mass contact campaign beginning on April 15, in which local leaders will interact with people to understand their problems.

At a roadside tea stall in Ahmedabad, Italia says, “The common people of Gujarat have started identifying with AAP.” Clad in blue jeans and white shirt, the 32-year-old law graduate and Surat resident used his stopover at the stall (even though he arrived in a Land Cruiser) to say, “I am truly an aam aadmi (common man). I can sit anywhere and interact with people.” According to Italia, AAP’s outreach will focus on education and health. Alleging that people are fed up with the “arrogance” of BJP leaders, he says, “No one listens to their grievances. Anyone can build schools, but this government’s mindset is dangerous. They are corrupting people’s minds.”

While AAP may have some of the youngest leaders in the state, none of them is a widely popular face. And it has nobody who can swing the votes of any caste group. However, Italia, a Leuva Patel, insists that Patidars, especially the youngsters among them, are not thinking along caste lines. “They will support anyone who has a vision for society irrespective of caste,” he says. However, allegations that Italia has made statements mocking Hindu gods may damage the party’s chances.

Meanwhile, AAP has started a publicity blitz on local TV channels, with Punjab CM Bhagwant Mann appearing every half an hour claiming his government has ended corruption in a week. Taking a leaf from Punjab, AAP has roped in its master strategist Sandeep Pathak, a Rajya Sabha member and former IIT-Delhi professor, to chalk out a plan for Gujarat. Pathak toured Ahmedabad for two days and announced on April 4 that AAP’s internal survey shows it could win 58 seats in the next election. “People of rural Gujarat are voting for us. The lower and middle class in urban areas too want a change and will vote for us,” he told reporters.

A source in the party, however, dismissed the report as exaggerated. “It is a tactic to boost our workers’ morale. As of now, our biggest achievement is our presence in all 182 constituencies,” the source says. Political observer Kashikar points out that even though AAP has a known face in former journalist Isudan Gadhvi, the party needs to strengthen its grassroots-level organisation. “Without it, they can’t go beyond municipality elections,” he says. AAP had failed to open its account in the 2017 election. This time, it hopes to do much better.