It was a grand occasion where the two pillars of democracy—the executive and the judiciary—came together to create frameworks for faster and inclusive delivery of justice in India. Held after a gap of five years, and addressed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chief Justice of India N.V. Ramana, the joint conference of chief ministers and chief justices of high courts at Delhi’s Vigyan Bhawan on April 30 laid bare one of the biggest challenges facing the judicial mechanism in the country—a serious shortage of judges, particularly in the high courts.

The 25 high courts across India have 1,104 positions for judges, but 378 of them lay vacant as on March 31, 2022. Nine new high court judges were appointed after the conference. In the lower judiciary, there are 24,521 posts for judges, but 5,180 are yet to be filled up as on April 7, 2022. In fact, the share of vacancies in the high courts has jumped since 2014—from 29 per cent to 35 per cent now—when the Narendra Modi-led government took charge at the Centre. This despite the fact that between 2014 and 2021, the Centre has been appointing annually an average of 92 High Court judges, up from 76, between 2006 and 2014. Besides, since 2014, the Union government has created 198 new positions for judges in the high courts. In the lower courts, the government has increased the number of seats for judges by over 5,000—and appointed many of them—in the past eight years, taking the total to 24,521. This has brought about a marginal decline in the share of vacant positions in these courts—from 23 per cent of the total sanctioned strength in 2014 to 21 per cent now.

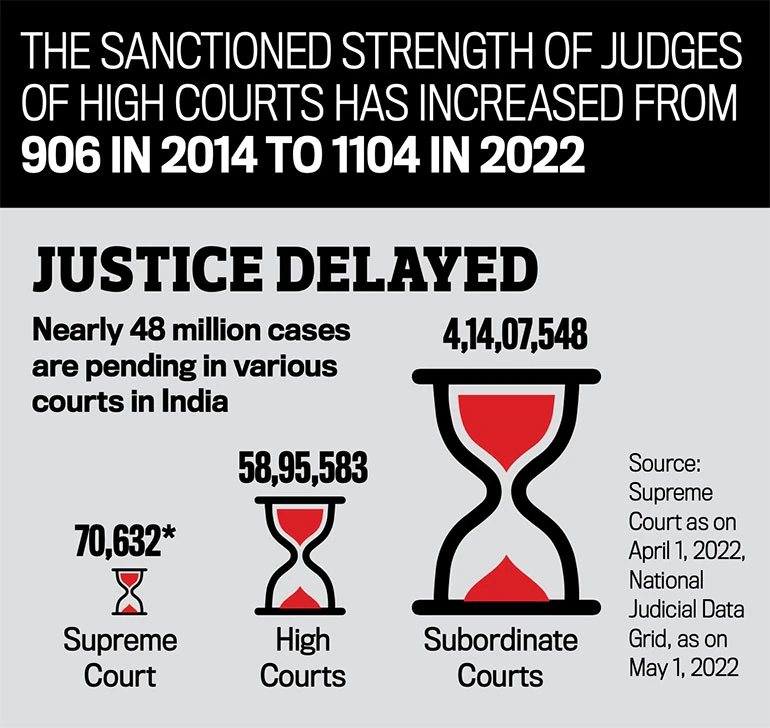

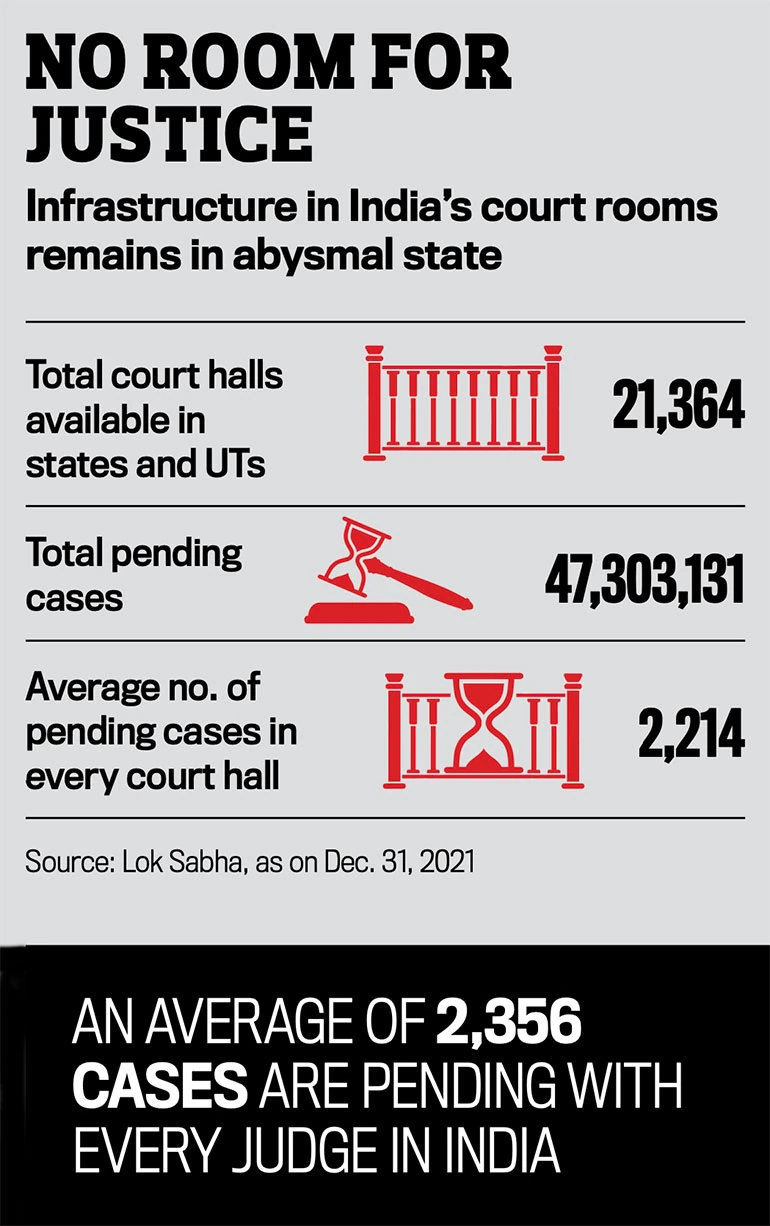

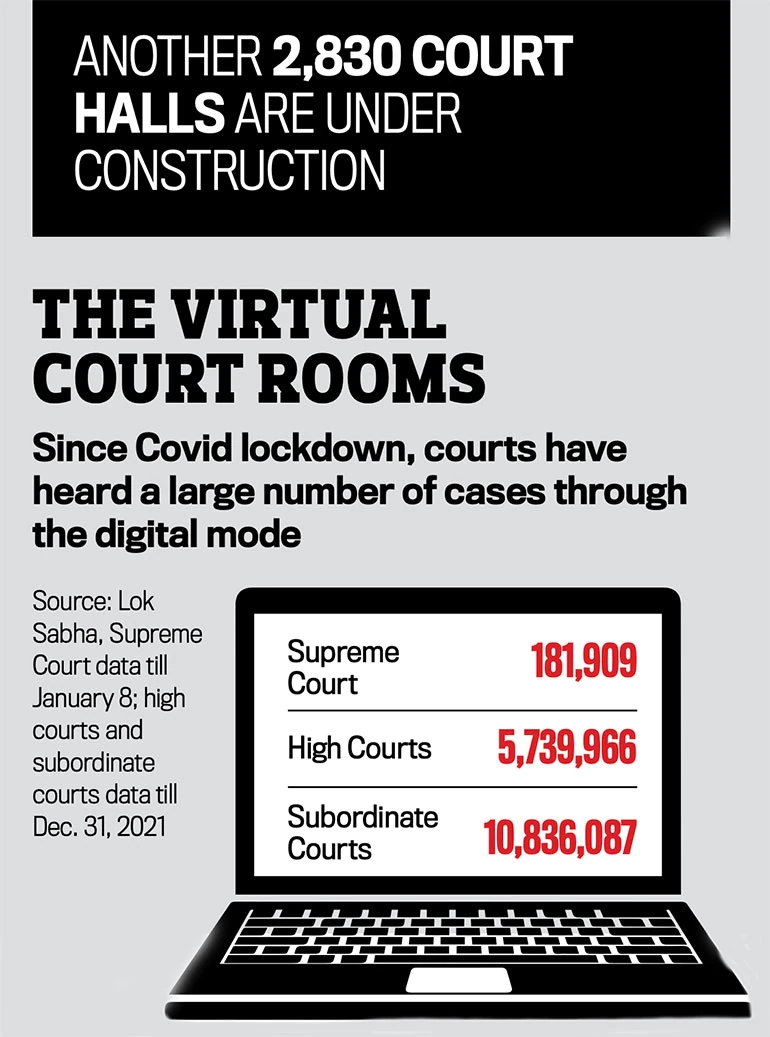

Undoubtedly, the spiralling vacancies have added to the judiciary’s burden, multiplying the ever-increasing case load. With nearly 48 million cases pending in various courts, every judge has an average pendency of 2,356 cases under his gavel. As Justice Ramana points out, despite an increase of judges in lower courts by 16 per cent since 2016, when the last conference was held, pendency of cases had gone up by 55 per cent. “The delay in hiring judges adds to the workload of incumbent ones and, consequently, reduces their efficiency. Most of our judges are working to keep up and clean up the rosters,” says Siddharth Luthra, a senior advocate in the Supreme Court.

How High Court Judges are appointed

Judicial appointments in the Supreme Court and high courts are largely governed by the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP), a collaborative framework between the executive and judiciary prepared in 1998. The process for the appointment of high court judges begins with the high court collegium—a body comprising the chief justice and other senior judges—recommending names for appointment. The recommendations are then sent to the state government, the Intelligence Bureau (IB) and the Union law ministry. Once cleared, the ministry forwards them to the Supreme Court collegium—consisting of the Chief Justice of India and other senior SC judges—for approval. The SC collegium sends the final recommendations to the law ministry. In case the government has any reservations, the name(s) are returned to the collegium for reconsideration. If it reiterates its recommendations, the Centre is bound to make the appointments.

Under the existing MoP, the high court collegium must make recommendations six months prior to the occurrence of vacancies. While the existing MoP doesn’t suggest any period within which the law ministry is supposed to forward the recommendations to the Supreme Court collegium, in 2021, the Supreme Court set down a period of 18 weeks to complete the process. The IB must give inputs on the names within eight weeks and the law ministry should process the names—following IB inputs—within four to six weeks. As already laid down in the MoP, the Supreme Court collegium must send its final recommendations to the Centre in the next four weeks.

Within the next three weeks, the law ministry must put the names of the prospective high court justices before the prime minister, who would advise the President on the appointments. No time limit has been prescribed for action by the PM and the President. While the central government can send back a name to the SC collegium for reconsideration, if the same name is reiterated by the collegium, the appointment must be made within three to four weeks. Earlier, the MoP did not lay down a timeline for cases when the collegium resends names.

Though this is what the process looks like on paper, none of the players follow any time-frame. Most legal observers concur that building consensus on names has always been time-consuming. The aspirant has to not only pass the intensive scrutiny of the collegiums, but also has to withstand the clearance of the executive. That last test can hinge on his/her family’s political affiliation, antecedents and any other “qualifying details”, which never come out in public. Neither the Union government nor the collegium system substantiates its decisions and recommendations with reasons.

CANDIDATES ARE EXAMINED BY THE EXECUTIVE. THEIR FAMILY’S POLITICAL AFFILIATIONS MAY BE SCRUTINISED, OR OTHER ‘QUALIFYING DETAILS’, WHICH NEVER COME OUT

The slow, first move

The delay first starts at the level of the high court collegiums. The timeline for recommending names six months prior to occurrence of vacancies is rarely followed. While there were 378 vacancies in high courts at the end of March, even the proposals for names from the high court collegiums did not come for 219 positions. Recently, the parliamentary standing committee on personnel, public grievances, law & justice headed by BJP Rajya Sabha MP Sushil Kumar Modi expressed dismay over delays in the sending of recommendations by the high court collegiums, as the date of vacancy of a post becomes known the day a judge assumes charge.

At the 39th Chief Justices’ Conference on April 29, Justice Ramana appealed to the high courts to expedite the process of sending the proposals to fill the vacancies. Arghya Sengupta, research director of Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, believes that judges are not to be blamed for the failure to send recommendations in time. “Judges cannot be expected to keep track of who is retiring when. It’s an administrative function that is not professionally managed in high courts and the Supreme Court. This causes delay in the first place. The solution lies in professionalising the judicial administration,” he says. Former Supreme Court judge and Chief Justice of Andhra Pradesh High Court Justice Madan Lokur points towards an institutional barrier. “The chief justice of a high court is always an outsider and he or she takes time to get familiar with the lawyers, their merit and integrity. This delays the process,” he says.

The rejection of recommendations by the government and the Supreme Court collegium also adds to the delay, as the high courts then have to find new names, starting the process all over again. According to Attorney-General K.K. Venugopal, around 35-40 per cent of names are rejected by the Supreme Court collegium. “There is complete lack of communication and an absence of transparency between the Supreme Court and the high courts in the manner of dealing with recommendations. The cause of rejection of recommendations is not known to the high court chief justice. So, rectification of an error is not possible,” says Justice Lokur.

Many legal experts say that high courts should send a larger pool of names so that even after rejections, enough names remain to fill vacancies. Even the Supreme Court has often emphasised that high court chief justices should recommend vacancies as early as possible, irrespective of whether their old recommendations were cleared or not.

That is easier said than done. Most judges in private claim that there is a huge shortage of suitable and willing candidates. A collegium cannot recommend the name of an unsuitable candidate simply because vacancies are increasing. It has to consider several factors, including performance and integrity of a candidate. These decisions take time, as opinions are often subjective. “We must not forget that removal of judges is far more difficult than appointing them. One erroneous appointment can disrupt the entire system,” says Supreme Court lawyer Utkarsh Singh.

Graphics by Asit Roy

Challenges of the Collegium

The delay also happens at the Supreme Court collegium level in clearing names. In 2020, Venugopal submitted to the apex court that the average time taken by the collegium to clear names was 119 days or 17 weeks, as against four weeks recommended by the MoP. Apart from these delays, the collegium process has also been criticised for lacking transparency.

Prior to 2018, collegium recommendations were not made available in the public domain. It changed under the tenure of the then CJI Dipak Misra, who facilitated the publishing of collegium resolutions on the Supreme Court’s website. However, the reasons and rationale behind rejecting or accepting a name are still not published. The judicial fraternity is divided over public scrutiny of these decisions. There are fears that transparency about names under consideration may make the process longer, as every decision will be questioned. “Transparency can be brought in after the appointment process is complete. After a cooling-off period, details of proceedings may be disclosed appropriately, without putting question marks on anyone’s integrity,” says lawyer Singh.

There was even an attempt to disband the collegium system. To streamline judicial appointments, the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) was created through a constitutional amendment; the NJAC Act was passed in April 2015. The NJAC was supposed to be a body comprising three senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, the Union law minister and two eminent persons appointed by the CJI, prime minister and leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha. However, within months of the NJAC coming into force, it was struck down as unconstitutional by the apex court. “One of the members of that Supreme Court bench later regretted striking it down, saying it was wrong. But what’s the point now? Had the NJAC been in place, things would have been different and more transparent,” Union law minister Kiren Rijiju said.

Executive Delay

The third cog in this process is the central government, whom the apex court has continuously criticised over the vacancies. Under Ramana’s tenure, the Supreme Court Collegium made 180 recommendations for appointments in various high courts, but the government is yet to clear 45 names. A total of 159 recommendations from the past are still pending with the Centre. By the government’s own admission, after receiving IB inputs on names recommended by the High Court collegium, it takes 127 days or 18 weeks to send the same to the Supreme Court collegium. On being questioned by the apex court about this long period, Venugopal said: “Suppose there is an adverse IB report, we have to verify it. We cannot blindly forward it.”

UNDER RAMANA’S TENURE SINCE APRIL 2021, THE SC COLLEGIUM SENT 180 NAMES FOR APPOINTMENTS IN HIGH COURTS. THE CENTRE HASN’T CLEARED 45 NAMES

Some even seek to attribute political motives to these delays by the BJP-led Union government. Amongst the 25 high courts, the ones with the highest percentage of names still pending with the Centre are the Bombay High Court (65 per cent of all names sent by it to the Union law ministry), Calcutta High Court (47 per cent) and Rajasthan High Court (33 per cent). Critics point out that these courts are located in states governed by non-BJP parties. They also have a very high share of vacancies—48 per cent of the total sanctioned strength of judges in the Rajasthan High court, 46 per cent in the Calcutta High Court and 38 per cent in the Bombay High Court.

However, BJP-ruled states fare no better, going by the percentages of judges’ vacancies in their high courts. For instance, 48 per cent of the sanctioned strength of judges in the Patna High Court lie vacant; 42 per cent in the Allahabad High Court and and 38 per cent in the Gujarat High Court. Even during UPA rule, judicial vacancies in high courts hovered around 30 per cent. The bigger problem lies with names that are not cleared despite having been re-sent by the collegium several times. Between January 1, 2021 and February 1, 2022, the SC collegium reiterated 29 recommendations at least once. The Centre had cleared none till April 11.

“The delay in clearing reiterated appointments is a way of the executive telling the SC that we are the masters of appointments, regardless of your opinion. Besides, the waiting time has significantly increased in the past few years and, more worryingly, in selective cases. The Union law minister and the Chief Justice of India should sort out these and other problems,” says Justice Lokur.

Legal experts say that such delays, despite multiple reiterations by the SC collegium, can demoralise potential candidates. The apex court has said that keeping names pending for long periods does little to encourage senior lawyers to join the judgeship. The Sushil Modi-led standing committee has also pointed out its effects—because of delays in appointments, many lawyers have started saying no to such appointments.

DELAYS IN THE APPOINTMENT OF JUDGES DESPITE REITERATIONS BY THE SC COLLEGIUM DO NOT ENCOURAGE SENIOR LAWYERS TO JOIN THE JUDGESHIP

For instance, in February 2022, senior advocate Aditya Sondhi withdrew his consent for elevation, citing a delay of a year. His name was recommended for a position of a judge at the Karnataka High Court in February 2021 and reiterated in September 2021. “No respectable lawyer is prepared to wait ad infinitum and thus there have been a spate of refusals by them,” read the Standing Committee report in March 2022.

Rijiju claims the government has “never deliberately” delayed appointments. Claiming that file clearances are much faster now, he pointed out that two apex court judges were appointed in May within 48 hours of recommendations. He also invoked the fact that the Supreme Court itself had stated that the government must act on the selection of judges only after proper due diligence, which takes time. In an affidavit filed in the apex court, the Centre said that it appointed 77 per cent of the judges recommended to various high courts by the SC collegium between January 1, 2021, and January 30, 2022. A Supreme Court order in 2019 said that the names on which the SC Collegium, the high courts and the governments had agreed upon should be appointed within six months. The affidavit claimed that the Centre took an average of 41 days, or six weeks, from the date of final resolution of the SC collegium to the appointment of judges in high courts.

The way forward

The parliamentary standing committee doesn’t seem impressed with the current pace. In its report, it categorically asserts that the “existing process is not working and needs to be re-engineered”. It cautions that no mechanism will be effective unless timelines for completion of various stages of the appointment process are not only firmly laid down but also scrupulously followed by all authorities.

But India’s problem of shortage of judges cannot be solved just by filling up vacancies. To achieve something like the judge-population ratio of leading countries, India needs to create more judges. In 1987, the Law Commission had recommended 50 judges per million people. Over three decades later, India has 21 judges per million persons. That too on the basis of sanctioned strength. There will be a steep dip if the actual working strength of judges is considered. Compare that to nearly 150 judges per million people in the US and China and over 50 in the UK.

Addition of manpower must start from lower courts, where recruitments happen either through state public service commissions or on recommendations by high courtss. In both, the state executive machinery plays a critical role. That’s the reason Justice Ramana urged chief ministers to increase the sanctioned strength of judicial officers in subordinate courts.

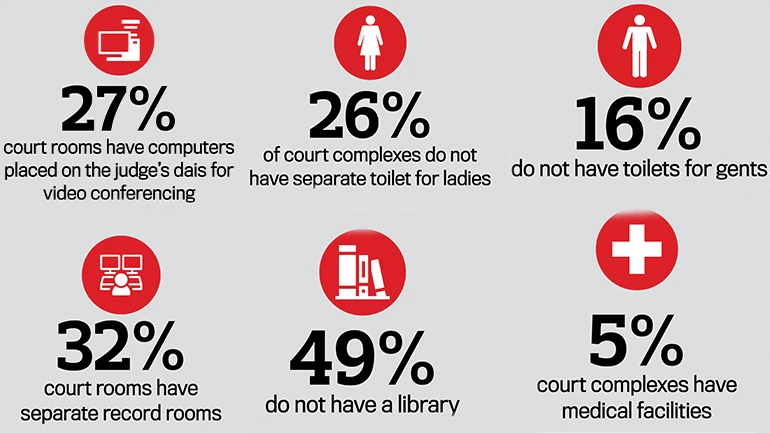

Not just more justices, judicial infrastructure too must be improved. Since 2014, the Centre has given the states Rs 5,565 crore under the centrally sponsored scheme for development of infrastructure facilities in district and subordinate courts. Yet, infrastructure remains abysmal. Only 27 per cent court rooms have computers placed on the judge’s dais for video conferencing; 26 per cent of court complexes do not have toilets for women, only 32 per cent of court rooms have separate record rooms, and 49 per cent courts don’t have libraries. Rude reminders that the judicial system in India is still limping along on crutches.